Happy Hallowe'en, Brethren and welcome to the final installment of Horror on the High Seas week. Whether you are sad to see it go or happy it's almost over, I hope you enjoyed something about our week of spine-tingling, grotesque and sometimes tragic tales.

Today, a ghost story. What could be more fitting for Hallowe'en? I first told this story online over at HoodooQ last April. It is familiar in many forms around southeastern Louisiana, where ghost pirates and buried treasure are a time honored tradition. The story was included in the Depression era collection Gumbo Ya~Ya, edited by Lyle Saxon. In Saxon's version, the island where the treasure is buried is called Isle de Gombi. In this version, the pirate is none other than Vincent Gambi himself.

So sit back, relax, bundle up if need be and allow yourself to slip away to an ancient, Louisiana bayou, where the frogs are chirping, the willow-the-wisps are flitting, and the drown just won't stay dead...

There was a quadroon man named Louis who lived on Bayou Grand Caillou. He was and fisherman. Sometimes he was happy with his trade. Sometimes he was not. Louis heard, from the other men who pulled oysters and mud bugs out of the bayou, that a nearby island was the spot where the Baratarian pirate Gambi had buried a horde of treasure. Now the talk went that Gambi was the most ruthless and treacherous of the pirates who aligned themselves with the famous Jean Laffite. He would slit a man's throat for no reason. It was said that if anyone tried to steal his buried treasure, his ghost would slit that man's throat as well.

Louis was a brave man if, it must be admitted, not very bright. He began to inquire about the pirate's treasure. His friends told him he was crazy. But Louis persisted. Finally one old Cajun told him that the only way to find Gambi's treasure was to go to the little island on a full moon night and look for a patch of moss that glowed silver. That was were the pirate had hidden his horde.

Being brave, if not very bright, Louis waited until the next full moon. Then he packed up his little pirogue with a shovel and canvas and everything he thought he would need to bring that treasure home. He sailed out to the deserted island, which as it turned out was no more than a muddy chenier. There was nothing there but a broken down boat shed, two sad cypress trees and big patches of green moss that looked black in the darkness.

Louis pulled his boat up high onto the broken shells of the island's shore. He looked around, hands on hips, almost sure that old Cajun had tricked him good. Then he saw it. A patch of moss that glowed like silver close to one of those scraggly trees.

He set to his task right away. The chuff and hiss of his spade, the croaking of frogs and his own breathing were the only sounds beside a mournful wind off the Gulf. But then Louis heard another sound, like something being dragged across the shells at the water's edge. He turned and was surprised to see his pirogue down in the water when he was sure he had dragged her high up on land. Throwing down his shovel, Louis marched into the water. He dragged that boat clear up to the other sorry cypress tree, and tied her to it.

Louis stomped back to the hole he had started, grumbling about the wind and the tide. Just as he was putting spade to soil he noticed four ugly, hairy feet with their toes just hanging over the edge of his little ditch. At that moment, Louis felt cold despite the heat. He gulped, although his mouth was dry as winter. Mustering all his dumb bravery, he looked up from his spade.

There stood two grinning, horrible pirates. They were sodden with water and seaweed. Mud bugs crawled through their beards and clothes. Their cutlasses dripped red with rust or blood - Louis did not want to know which. They stared at him with eyes that gleamed cold silver.

Now Louis was a good Catholic and he knew what to do when the Devil jumped up. He fell to his knees, crossed himself, and began to recite the Hail Mary over and over again. After his seventh sincere recitation of the prayer to the Virgin, Louis opened just one eye. Sure enough, those silver-eyed, watery pirated had disappeared and Louis, to his everlasting relief, was still alive.

As Louis' breathing settled down, he heard that awful scraping sound once again. Turning, he saw a third pirate sitting comfortably in his pirogue. This one wore a long dagger, held a fine ivory-handled pistol and sported a long, bristling black mustache. He was also dripping wet, covered with detritus and creatures from the Gulf and wearing high leather boots that marked him as a man in charge.

"Gambi?" Louis ventured.

"At your service," the phantom replied. "And if you do not get in this pathetic dinghy and row for your life, I will shoot you for no good reason." Gambi smiled a wicked smile. One gold tooth gleamed like fire in the moonlight.

Louis didn't need to hear that order twice. Abandoning his tools, he untied his boat, jumped in and began to row. He rowed as hard as he knew how while the pirate sat across from him, grinning and pointing his pistol and Louis' gut.

Once the pirogue was a few leagues out in the bayou, Gambi's ghost put away his ancient pistol. Without another word, he slipped over the side of the boat and disappeared into the black paint water. Louis would later say that he knew for truth the creature was not of this Earth as no bubbles rose to the surface when it sank.

So Louis went straight home and there is wife nearly shot him herself, for he looked so different. His hair had turned white to a strand and he would never smile again. Though he told his story to anyone who would listen as though trying to relieve himself of memory, it wasn't long before Louis went to bed one night and died right there in his sleep. Rumor among the fishermen said that old Louis had joined the phantom pirates on that chenier off Bayou Grand Caillou...

Header: The Pirate's Ghost by Howard Pyle via Wikimedia

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Horror on the High Seas: Of Lice and Sailors

Horror is not always about things done to us against our will - hauntings, tragedies, torture - sometimes our own bodies are invaded with horrors. Or produce them. That is the stomach-churning subject of today's post.

In 1480, Friar Felix Faber, a Dominican monk from the Swabian city of Ulm, set out on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. This was a popular undertaking at the time what with spiritual favors and dispensations available from the Catholic Church if one made the trip. The popularity of such travel created its own problems, however. People unaccustomed to shipboard life crammed together like olives in a jar was a recipe for personal and public disaster. And Friar Felix wrote it all down for posterity.

On parasites, and lice in particular:

On a boat, too many people travel without a change of clothing; they live in sweat and foul odors, in which vermin thrive, not only in clothing but also in beards and hair. Therefore the pilgrim must not be lax; he must cleanse himself daily. A person who has not a single louse right now can have thousands an hour from now if he has the slightest contact with an infested pilgrim or sailor. Take care of the beard and the hair every day, for if the lice proliferate you will be obliged to shave your beard and thus lose your dignity, for it is scandalous not to wear a beard at sea. On the other hand, it is pointless to keep a long head of hair, as do some nobles unwilling to make the sacrifice. I have seen them so covered with lice that they gave them to all their friends and troubled all their neighbors. A pilgrim should not be ashamed to ask others to scour his beard for lice.

Friar Faber's "zest for the pen," as his translator Arthur Goldhammer puts it in The History of Private Life: Revalations of the Medieval World, actually makes one's skin itch as they read that paragraph. The interesting point, at least to me, is that the good Friar admonishes the pilgrim to "cleanse himself daily," something many historians have previously discounted as even possible aboard ship. But Friar Felix does not spare his reader much if anything in the way of instruction...

On elimination at sea:

Each pilgrim has near his bed a urinal - a vessel of terra-cotta, a small bottle - into which he urinates and vomits. But since the quarters are cramped for the number of people, and dark besides, and since there is much coming and going, it is seldom that these vessels are not overturned before dawn. Quite regularly in facts, driven by a pressing urge the obliges him to get up, some clumsy fellow will knock over five or six urinals in passing, giving rise to an intolerable stench.

In the morning, when the pilgrims get up and their stomachs ask for grace, they climb the bridge and head for the prow, where on either side of the spit privies have been provided. Sometimes as many as thirteen people or more will line up for a turn at the seat, and when someone takes too long it is not embarrassment but irritation that is expressed...

At night, it is a difficult business to approach the privies owing to the huge number of people lying or sleeping on the decks from one end of the galley to the other. Anyone who wants to go must climb over more than forty people, stepping on them as he goes; with every step he risks kicking a fellow passenger or falling on top of a sleeping body. If he bumps into someone along the way, insulst fly. Those without fear or vertigo can climb up to the prow along the ship's gunwales, pushing themselves along from rope to rope, which I often did despite the risk, and the danger. By climbing out the hatches to the oars, one can slide along in a sitting position from oar to oar, but this is not for the faint of heart, for straddling the oars is dangerous, and even the sailors do not like it.

But the difficulties become really serious in bad weather., when the privies are constantly inundated by waves and the oars are shipped and laid across the benches. To go to the seat in the middle of a storm is thus to risk being completely soaked, so that many passengers remove their clothing and go stark naked. But in this, modesty suffers greatly, which only stirs the shameful parts even more. Those who do not wish to be seen this way go squat in other places, which they soil, causing tempers to flare and fights to break out, discrediting even honorable people. Some even fill their vessels near their beds, which is disgusting and poisons the neighbors and can be tolerated only in invalids, who cannot be blamed: a few words are not enough to recount what I was forced to endure on account of a sick bedmate.

Despite all these myriad hardships, Friar Felix is very clear that one should not avoid the privy at sea. In fact, he recommends visiting it three or four times a day "even when there is no natural urge" to avoid constipation. He warns that pills or suppositories to help nature along are not "safe" aboard ship because "to purge oneself too much can cause worse trouble than constipation." It is easy to imagine what type of trouble the Friar implies.

Even with all the hardships, Friar Faber went to the Holy Land twice. One wonders, however, how many of his fellow Dominicans and others who had the privileged to be able to read were discouraged by his conversational and graphic descriptions of the nitty-gritty of sea travel at the time.

Header: Ship of Fools by Pieter van der Heyden c 1559 via Wikimedia

In 1480, Friar Felix Faber, a Dominican monk from the Swabian city of Ulm, set out on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. This was a popular undertaking at the time what with spiritual favors and dispensations available from the Catholic Church if one made the trip. The popularity of such travel created its own problems, however. People unaccustomed to shipboard life crammed together like olives in a jar was a recipe for personal and public disaster. And Friar Felix wrote it all down for posterity.

On parasites, and lice in particular:

On a boat, too many people travel without a change of clothing; they live in sweat and foul odors, in which vermin thrive, not only in clothing but also in beards and hair. Therefore the pilgrim must not be lax; he must cleanse himself daily. A person who has not a single louse right now can have thousands an hour from now if he has the slightest contact with an infested pilgrim or sailor. Take care of the beard and the hair every day, for if the lice proliferate you will be obliged to shave your beard and thus lose your dignity, for it is scandalous not to wear a beard at sea. On the other hand, it is pointless to keep a long head of hair, as do some nobles unwilling to make the sacrifice. I have seen them so covered with lice that they gave them to all their friends and troubled all their neighbors. A pilgrim should not be ashamed to ask others to scour his beard for lice.

Friar Faber's "zest for the pen," as his translator Arthur Goldhammer puts it in The History of Private Life: Revalations of the Medieval World, actually makes one's skin itch as they read that paragraph. The interesting point, at least to me, is that the good Friar admonishes the pilgrim to "cleanse himself daily," something many historians have previously discounted as even possible aboard ship. But Friar Felix does not spare his reader much if anything in the way of instruction...

On elimination at sea:

Each pilgrim has near his bed a urinal - a vessel of terra-cotta, a small bottle - into which he urinates and vomits. But since the quarters are cramped for the number of people, and dark besides, and since there is much coming and going, it is seldom that these vessels are not overturned before dawn. Quite regularly in facts, driven by a pressing urge the obliges him to get up, some clumsy fellow will knock over five or six urinals in passing, giving rise to an intolerable stench.

In the morning, when the pilgrims get up and their stomachs ask for grace, they climb the bridge and head for the prow, where on either side of the spit privies have been provided. Sometimes as many as thirteen people or more will line up for a turn at the seat, and when someone takes too long it is not embarrassment but irritation that is expressed...

At night, it is a difficult business to approach the privies owing to the huge number of people lying or sleeping on the decks from one end of the galley to the other. Anyone who wants to go must climb over more than forty people, stepping on them as he goes; with every step he risks kicking a fellow passenger or falling on top of a sleeping body. If he bumps into someone along the way, insulst fly. Those without fear or vertigo can climb up to the prow along the ship's gunwales, pushing themselves along from rope to rope, which I often did despite the risk, and the danger. By climbing out the hatches to the oars, one can slide along in a sitting position from oar to oar, but this is not for the faint of heart, for straddling the oars is dangerous, and even the sailors do not like it.

But the difficulties become really serious in bad weather., when the privies are constantly inundated by waves and the oars are shipped and laid across the benches. To go to the seat in the middle of a storm is thus to risk being completely soaked, so that many passengers remove their clothing and go stark naked. But in this, modesty suffers greatly, which only stirs the shameful parts even more. Those who do not wish to be seen this way go squat in other places, which they soil, causing tempers to flare and fights to break out, discrediting even honorable people. Some even fill their vessels near their beds, which is disgusting and poisons the neighbors and can be tolerated only in invalids, who cannot be blamed: a few words are not enough to recount what I was forced to endure on account of a sick bedmate.

Despite all these myriad hardships, Friar Felix is very clear that one should not avoid the privy at sea. In fact, he recommends visiting it three or four times a day "even when there is no natural urge" to avoid constipation. He warns that pills or suppositories to help nature along are not "safe" aboard ship because "to purge oneself too much can cause worse trouble than constipation." It is easy to imagine what type of trouble the Friar implies.

Even with all the hardships, Friar Faber went to the Holy Land twice. One wonders, however, how many of his fellow Dominicans and others who had the privileged to be able to read were discouraged by his conversational and graphic descriptions of the nitty-gritty of sea travel at the time.

Header: Ship of Fools by Pieter van der Heyden c 1559 via Wikimedia

Monday, October 29, 2012

Horror on the High Seas: The Sinking of HMS Bounty

I had a lovely post about mermaids eating people (seriously; the originals did that) planned for today, but this morning's tragic loss of the HMS Bounty warrants more attention than women with fish tails. Hurricane Sandy has claimed a little piece of history, and two of her crew are still missing. This is the kind of horror that our ancestors faced every time they put out to sea, and here it is right in front of us.

From Bounty's Facebook page:

We received a distress call from Bounty at 1830 Sunday evening that the Ship lost power and her pumps were unable to keep up with the dewatering. At that time we immediately contacted the USCG for assistance.

Bounty had departed Connecticut late last week bound for St. Petersburg, Florida according to Hampton Roads online via the HMS Bounty Organization. The ship, manned by a crew of 16, hoped to sail around the hurricane. It is reasonable to imagine that no one knew at the time Bounty set out just how formidably large Sandy would become.

The Coast Guard managed to rescue 14 members of the crew, all of whom had abandon ship when Bounty took on more water than her pumps could handle. The men were lifted into Jayhawk helicopters and taken safely to the Coast Guard Air Station at Elizabeth City, North Carolina. The other 2 crewmen, who as of this writing have yet to be found, were reported to be in survival suits and wearing personal floatation devises. The search continues for both sailors.

Bounty, a 180 foot three masted frigate-type, was built in 1962 for the Marlon Brando vehicle Mutiny on the Bounty. She has been used in several movies since, most notably Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean series. She now rests below wave off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

Though the loss of Bounty is surely felt by those of us who love the sea, in the immortal words of Dominique Youx, one can always get another ship. I'm sure I speak for the Brethren when I say that our hearts go out to those who love the men still missing, and we pray for their quick and safe return.

Header: HMS Bounty July, 2010; Assoc Press file photo by Mark Duncan via Hampton Roads

Update 6:40 PM Alaska Time:

According to HMS Bounty's Facebook page, one of the two missing crewmen, Claudene Christian, has been found. She has, tragically, passed away. Bounty's captain is now the only mariner still missing. Please keep everyone involved in this horrible tragedy in your thoughts and prayers.

Update 8:01 AM Alaska Time:

Please see the comments on this post and/or continue to check HMS Bounty's Facebook page for updated information. As of this writing, Captain Walbridge has not yet been located. Please continue to send positive energy his way; we pray for his safe return.

From Bounty's Facebook page:

We received a distress call from Bounty at 1830 Sunday evening that the Ship lost power and her pumps were unable to keep up with the dewatering. At that time we immediately contacted the USCG for assistance.

Bounty had departed Connecticut late last week bound for St. Petersburg, Florida according to Hampton Roads online via the HMS Bounty Organization. The ship, manned by a crew of 16, hoped to sail around the hurricane. It is reasonable to imagine that no one knew at the time Bounty set out just how formidably large Sandy would become.

The Coast Guard managed to rescue 14 members of the crew, all of whom had abandon ship when Bounty took on more water than her pumps could handle. The men were lifted into Jayhawk helicopters and taken safely to the Coast Guard Air Station at Elizabeth City, North Carolina. The other 2 crewmen, who as of this writing have yet to be found, were reported to be in survival suits and wearing personal floatation devises. The search continues for both sailors.

Bounty, a 180 foot three masted frigate-type, was built in 1962 for the Marlon Brando vehicle Mutiny on the Bounty. She has been used in several movies since, most notably Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean series. She now rests below wave off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

Though the loss of Bounty is surely felt by those of us who love the sea, in the immortal words of Dominique Youx, one can always get another ship. I'm sure I speak for the Brethren when I say that our hearts go out to those who love the men still missing, and we pray for their quick and safe return.

Header: HMS Bounty July, 2010; Assoc Press file photo by Mark Duncan via Hampton Roads

Update 6:40 PM Alaska Time:

According to HMS Bounty's Facebook page, one of the two missing crewmen, Claudene Christian, has been found. She has, tragically, passed away. Bounty's captain is now the only mariner still missing. Please keep everyone involved in this horrible tragedy in your thoughts and prayers.

Update 8:01 AM Alaska Time:

Please see the comments on this post and/or continue to check HMS Bounty's Facebook page for updated information. As of this writing, Captain Walbridge has not yet been located. Please continue to send positive energy his way; we pray for his safe return.

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Horror on the High Seas: Return of the Man from Olon

It was the custom of L'Olonnois that, having tormented any persons and they not confessing, he would instantly cut them to pieces with his hanger, first some flesh, then a hand, an arm, a leg, and pull out their tongues.

~ Alexander Exquemelin in The Buccaneers of America

Doctor Exquemelin is, of course, talking about Francois L'Olonnais. Born David Nau in Olon, France, L'Olonnais ("the man from Olon") became one of the most infamously blood thirsty of the buccaneers. His most notorious act of cruelty, in which he slit open a man's chest with his cutlass (or "hanger"), pulled out the man's heart, took a bite from it and then shoved it into the mouth of the man's mate, is depicted above in a woodcut from the book.

~ Alexander Exquemelin in The Buccaneers of America

Doctor Exquemelin is, of course, talking about Francois L'Olonnais. Born David Nau in Olon, France, L'Olonnais ("the man from Olon") became one of the most infamously blood thirsty of the buccaneers. His most notorious act of cruelty, in which he slit open a man's chest with his cutlass (or "hanger"), pulled out the man's heart, took a bite from it and then shoved it into the mouth of the man's mate, is depicted above in a woodcut from the book.

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Horror on the High Seas: Dead

The word dead has a lot to do with Hallowe'en, which if we're honest is a celebration of the dead. So what better word for our Sailor Mouth Saturday during Horror on the High Seas week? I mean, we did devil last year.

We've discussed dead reckoning before, that amazing ability of our ancestors to make an educated guess about the positioning of their ship in blue water without reference to the stars or the planets. A keen trick if you could pull it off, but potentially deadly if your guess was wrong.

Many times the word dead has to do with components of a ship or her rigging. Dead doors are those attached to the inner bulwark of a ship's quarter gallery, this being the private latrine of the commanding officer. Since the quarter gallery is shifted slightly outward from the hull - for obvious reasons - dead doors are set in place to keep water out should the quarter gallery proper be, as Admiral Smyth puts it, "carried away." Wooden blocks, often made of elm, are used as stationary harnesses for rope to pass through; these blocks are known as dead eyes which comes from the older term, dead man's eyes. It is thought that the "dead" in this instance refers to the blocks' lack of movement.

The timber just at the midship bend, about a third of the length from her head, is known as a dead-flat. The dead-rising, by contrast, is the area of a ship near the stern post and is usually a reference to her bottom rather than her deck. Dead ropes are those which do not run through a block. Dead wood is used to correct certain inherent aberrations in a ship's keel; the blocks used were known individually as dead wood knees. Dead works refers to the entire part of the ship which is above the water line when that ship is fully laden.

Dead lights are the shutters which can be attached to the outside of the stern windows which light the commanding officer's cabin in larger ships. These are fastened shut in anticipation of dirty weather. Dead lights is also a term for swamp gas or the elusive jack-o-lantern.

Dead can also be applied to weather conditions and navigation. A dead calm indicates no wind whatever, a sailor's nightmare. This is similar to a dead-lown, which Admiral Smyth tells us in The Sailor's Word Book is a "completely still atmosphere." Dead on end refers to a full backing wind blowing in the exact opposite direction from the ship's course. Dead upon a wind is to slightly better advantage with the ship braced up and close hauled while hard tacking.

The dead months signified winter, and a dead lift was the act of moving a "very inert body" - perhaps your fallen mate. Dead weight is the amount a merchant vessel must pay for goods she did not ship. Dead pay was that given for a man on a ship's books who did not appear when compensation was handed out; as the Admiral puts it "as was formerly practiced with widow's men."

Dead men's effects were those sold via auction at the main mast when a mate died. The purchaser would often have his pay docked in the ship's books to compensate for whatever he had won at auction. This was not always done for each man, but was often reserved for those who had no family to return any belongings to.

A dead ticket is a document, signed by surgeon and commanding officer, that certifies the man is in fact dead at sea. This was the first step to clearing the seaman off the ship's books.

Finally there is the curious ritual of the dead horse, which was performed on merchant vessels. When work for which the seaman were paid via advance, such as preparing to put out to sea, was completed, the men - at least in theory - would once again begin earning new funds. At this point the effigy of a dead horse was dragged around the decks to represent the end of "fruitless labor." The doll horse was sometimes run up the yardarm thereafter and cast overboard, according to Admiral Smyth "amidst loud cheers." Now there's something most of us have never heard of but that was probably witnessed by more than one traveler in the 19th century.

And so an end to our discussion of dead. Horror on the High Seas week continues on the morrow and marches right on to Hallowe'en. Don't miss a minute, Brethren.

Header: Moonlit Night by Stefan Popowski c 1910 via Old Paint

We've discussed dead reckoning before, that amazing ability of our ancestors to make an educated guess about the positioning of their ship in blue water without reference to the stars or the planets. A keen trick if you could pull it off, but potentially deadly if your guess was wrong.

Many times the word dead has to do with components of a ship or her rigging. Dead doors are those attached to the inner bulwark of a ship's quarter gallery, this being the private latrine of the commanding officer. Since the quarter gallery is shifted slightly outward from the hull - for obvious reasons - dead doors are set in place to keep water out should the quarter gallery proper be, as Admiral Smyth puts it, "carried away." Wooden blocks, often made of elm, are used as stationary harnesses for rope to pass through; these blocks are known as dead eyes which comes from the older term, dead man's eyes. It is thought that the "dead" in this instance refers to the blocks' lack of movement.

The timber just at the midship bend, about a third of the length from her head, is known as a dead-flat. The dead-rising, by contrast, is the area of a ship near the stern post and is usually a reference to her bottom rather than her deck. Dead ropes are those which do not run through a block. Dead wood is used to correct certain inherent aberrations in a ship's keel; the blocks used were known individually as dead wood knees. Dead works refers to the entire part of the ship which is above the water line when that ship is fully laden.

Dead lights are the shutters which can be attached to the outside of the stern windows which light the commanding officer's cabin in larger ships. These are fastened shut in anticipation of dirty weather. Dead lights is also a term for swamp gas or the elusive jack-o-lantern.

Dead can also be applied to weather conditions and navigation. A dead calm indicates no wind whatever, a sailor's nightmare. This is similar to a dead-lown, which Admiral Smyth tells us in The Sailor's Word Book is a "completely still atmosphere." Dead on end refers to a full backing wind blowing in the exact opposite direction from the ship's course. Dead upon a wind is to slightly better advantage with the ship braced up and close hauled while hard tacking.

The dead months signified winter, and a dead lift was the act of moving a "very inert body" - perhaps your fallen mate. Dead weight is the amount a merchant vessel must pay for goods she did not ship. Dead pay was that given for a man on a ship's books who did not appear when compensation was handed out; as the Admiral puts it "as was formerly practiced with widow's men."

Dead men's effects were those sold via auction at the main mast when a mate died. The purchaser would often have his pay docked in the ship's books to compensate for whatever he had won at auction. This was not always done for each man, but was often reserved for those who had no family to return any belongings to.

A dead ticket is a document, signed by surgeon and commanding officer, that certifies the man is in fact dead at sea. This was the first step to clearing the seaman off the ship's books.

Finally there is the curious ritual of the dead horse, which was performed on merchant vessels. When work for which the seaman were paid via advance, such as preparing to put out to sea, was completed, the men - at least in theory - would once again begin earning new funds. At this point the effigy of a dead horse was dragged around the decks to represent the end of "fruitless labor." The doll horse was sometimes run up the yardarm thereafter and cast overboard, according to Admiral Smyth "amidst loud cheers." Now there's something most of us have never heard of but that was probably witnessed by more than one traveler in the 19th century.

And so an end to our discussion of dead. Horror on the High Seas week continues on the morrow and marches right on to Hallowe'en. Don't miss a minute, Brethren.

Header: Moonlit Night by Stefan Popowski c 1910 via Old Paint

Friday, October 26, 2012

Horror on the High Seas: A Sailor Man's Hallowe'en

It was never easy for Popeye trying to woo the always self-loathing Olive Oil, but when Bluto won't go home on Hallowe'en night, it can only get worse. Enjoy this very old timey cartoon on this delightful Friday. I'll spy ye tomorrow for more of Triple P's week long tribute to my favorite holiday.

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Horror on the High Seas: Torture for Torture's Sake

Hard to believe but it is that time again... For the fourth year in a row, Triple P celebrates a seagoing Hallowe'en with Horror on the High Seas week. What, after all, is more fun than mayhem, torture, ghosts and disgust at sea? Seriously, we'll discuss all of that and more.

Let us start out with torture and pirates via that story of the unfortunate Aaron Smith. Smith, a pilot and some-time surgeon aboard an English merchant, was captured by pirates in the Caribbean in 1822. Pressed into unwilling service due to his knowledge of the islands, Smith witnessed atrocities that he would later write about to great acclaim. His pamphlet The Atrocities of the Pirates, was published after he was tried and acquitted on charges of piracy. Of course his Victorian contemporaries, already in love with the gruesome, snapped up his writing and, for a short time, the pilot knew a modicum of fame.

Here is a sample involving a member of the pirate crew whom the captain accused of plotting mutiny:

[The Captain] threatened me with vengeance for my interference, declaring that he had not done half that he intended to do.

Having said this, he turned to the man, told him that he should be killed, and therefore advised him to prepare for death, or confess himself to any of the crew whom I chose to call aside for that purpose.

The man persisted in his plea of innocence, declared that he had nothing to confess, and entreated them all to spare his life. They paid no attention to his assertions but, by the order of the Captain, the man was put into the boat, pinioned and lashed in the stern, and five of the crew were directed to arm themselves with pistols and muskets and to go in her. The captain then ordered me to go with them, savagely remarking that I should now see how he punished rascals, and giving directions to the boat's crew to row for three hours backwards and forwards through a narrow creek formed by a desert island and the island of Cuba. "I will see," cried he, exulting, "whether the mosquitoes & the sandflies will not make him confess." Prior to our leaving the schooner, the thermometer was above ninety degrees in the shade, and the poor wretch was now exposed naked to the full heat of the sun. In this state we took him to the channel, one side of which was bordered by swamps full of mangrove trees, and swarming with the venomous insects before mentioned.

We had scarcely been half an hour in this place when the miserable victim was distracted with pain; his body began to swell, and he appeared one complete blister from head to foot. Often in the agony of his torments did he implore them to end his existence and release him from his misery; but the inhuman wretches only imitated his cries, and mocked and laughed at him. In a very short time, from the effects of the solar heat and the stings of the mosquitoes and sandlies, his face had become so swollen that not a feature was distinguishable; his voice began to fail, & his articulation was no longer distinct.

The unfortunate man continued to be tortured in this manner for another half an hour. Finally, the boat was rowed back to the ship but, when the captain was informed that the man had not confessed, he ordered that the "rascal" be taken back to the sand bar and used for target practice. Surviving this, the poor devil was finally weighed down with "a pig of iron... fastened round his neck, & he was thrown into the sea."

An ignominious end for a man who clearly chose bad company and, in the final analysis, found a miserable death for it.

Header: Dead Pirate Ashore by Howard Pyle c 1887 via Wikipedia

Let us start out with torture and pirates via that story of the unfortunate Aaron Smith. Smith, a pilot and some-time surgeon aboard an English merchant, was captured by pirates in the Caribbean in 1822. Pressed into unwilling service due to his knowledge of the islands, Smith witnessed atrocities that he would later write about to great acclaim. His pamphlet The Atrocities of the Pirates, was published after he was tried and acquitted on charges of piracy. Of course his Victorian contemporaries, already in love with the gruesome, snapped up his writing and, for a short time, the pilot knew a modicum of fame.

Here is a sample involving a member of the pirate crew whom the captain accused of plotting mutiny:

[The Captain] threatened me with vengeance for my interference, declaring that he had not done half that he intended to do.

Having said this, he turned to the man, told him that he should be killed, and therefore advised him to prepare for death, or confess himself to any of the crew whom I chose to call aside for that purpose.

The man persisted in his plea of innocence, declared that he had nothing to confess, and entreated them all to spare his life. They paid no attention to his assertions but, by the order of the Captain, the man was put into the boat, pinioned and lashed in the stern, and five of the crew were directed to arm themselves with pistols and muskets and to go in her. The captain then ordered me to go with them, savagely remarking that I should now see how he punished rascals, and giving directions to the boat's crew to row for three hours backwards and forwards through a narrow creek formed by a desert island and the island of Cuba. "I will see," cried he, exulting, "whether the mosquitoes & the sandflies will not make him confess." Prior to our leaving the schooner, the thermometer was above ninety degrees in the shade, and the poor wretch was now exposed naked to the full heat of the sun. In this state we took him to the channel, one side of which was bordered by swamps full of mangrove trees, and swarming with the venomous insects before mentioned.

We had scarcely been half an hour in this place when the miserable victim was distracted with pain; his body began to swell, and he appeared one complete blister from head to foot. Often in the agony of his torments did he implore them to end his existence and release him from his misery; but the inhuman wretches only imitated his cries, and mocked and laughed at him. In a very short time, from the effects of the solar heat and the stings of the mosquitoes and sandlies, his face had become so swollen that not a feature was distinguishable; his voice began to fail, & his articulation was no longer distinct.

The unfortunate man continued to be tortured in this manner for another half an hour. Finally, the boat was rowed back to the ship but, when the captain was informed that the man had not confessed, he ordered that the "rascal" be taken back to the sand bar and used for target practice. Surviving this, the poor devil was finally weighed down with "a pig of iron... fastened round his neck, & he was thrown into the sea."

An ignominious end for a man who clearly chose bad company and, in the final analysis, found a miserable death for it.

Header: Dead Pirate Ashore by Howard Pyle c 1887 via Wikipedia

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

Tools of the Trade: Relaxing at Sea

Aside from alcohol, the habit of choice among seaman during the Great Age of Sail was tobacco. Time off, what there was of it, at sea often meant enjoying a pipe or a cigar. One can find examples of this habit all over the written record - Dampier, Exquemelin and others mention pipe smoking among the buccaneers, for instance. It also shows up in nautical fiction; both Hornblower and Aubrey were known to enjoy a cigar now and then.

According to Peter H. Spectre in his A Mariner's Miscellany the habit had an edge of the caste system to it. Simple seamen were more likely to indulge in pipe smoking - when they were allowed to smoke - while officers preferred more expensive cigars. Seamen generally mixed their own pipe tobacco, and Spectre generously offers a recipe for same:

Mix 72% Burley tobacco with 25% Virginia and 3% Latakia. He also advises:

To prevent the tobacco from burning rapidly in windy conditions at sea, the cut should be coarse - cube, or moderately thick flake.

This was a critical issue not only from the standpoint of waste but also for fear of fire. Sparks on a wooden ship covered with tar and carrying black powder were a fearsome threat. Losing one's wooden island in the middle of blue water was unthinkable, so certain areas - the galley in particular, where fire was a necessary evil - were designated for smoking.

When the sea and/or wind made smoking impossible or unusually dangerous, tobacco was often chewed. So called "plug" tobacco was mixed by the user, formed into a cake and wrapped in canvas. The user would then cut or tear a piece off for chewing. Once again, Spectre offers a recipe which actually does not sound as unappealing as one might imagine:

Tobacco leaves were soaked in honey, molasses, or other flavored syrup. A hole as drilled into a baulk of wood - hickory was preferred, but other species served in a pinch - and the sodden tobacco was forced into it (hence the word "plug"). Once the tobacco had cured, the plug was pulled from the hole and wrapped in canvas, ready for use.

Though the smoking of pipes on a fine day would have been possible while applying one's self to work like mending sails or making rope, chewing would have been more convenient. Either way it was a habit that seamen fell into easily. And one that was probably hard not to pursue by land as well.

Header: The Smoker by Adriaen van Ostade c 1640 via Wikipedia

According to Peter H. Spectre in his A Mariner's Miscellany the habit had an edge of the caste system to it. Simple seamen were more likely to indulge in pipe smoking - when they were allowed to smoke - while officers preferred more expensive cigars. Seamen generally mixed their own pipe tobacco, and Spectre generously offers a recipe for same:

Mix 72% Burley tobacco with 25% Virginia and 3% Latakia. He also advises:

To prevent the tobacco from burning rapidly in windy conditions at sea, the cut should be coarse - cube, or moderately thick flake.

This was a critical issue not only from the standpoint of waste but also for fear of fire. Sparks on a wooden ship covered with tar and carrying black powder were a fearsome threat. Losing one's wooden island in the middle of blue water was unthinkable, so certain areas - the galley in particular, where fire was a necessary evil - were designated for smoking.

When the sea and/or wind made smoking impossible or unusually dangerous, tobacco was often chewed. So called "plug" tobacco was mixed by the user, formed into a cake and wrapped in canvas. The user would then cut or tear a piece off for chewing. Once again, Spectre offers a recipe which actually does not sound as unappealing as one might imagine:

Tobacco leaves were soaked in honey, molasses, or other flavored syrup. A hole as drilled into a baulk of wood - hickory was preferred, but other species served in a pinch - and the sodden tobacco was forced into it (hence the word "plug"). Once the tobacco had cured, the plug was pulled from the hole and wrapped in canvas, ready for use.

Though the smoking of pipes on a fine day would have been possible while applying one's self to work like mending sails or making rope, chewing would have been more convenient. Either way it was a habit that seamen fell into easily. And one that was probably hard not to pursue by land as well.

Header: The Smoker by Adriaen van Ostade c 1640 via Wikipedia

Monday, October 22, 2012

Literature: The Moral in the Knot

Amongst others, he taught me a fisherman's bend, which he pronounced to be the king of all knots; "and Mr. Simple," continued he, "there is a moral in that knot. You observe, that when the parts are drawn the right way, and together, the more you pull the faster they hold, and the more impossible to untie them; but see, by hauling them apart, how a little difference, a pull the other way, immediately disunites them, and then how easy they cast off in a moment. That points out the necessity of pulling together in this world, Mr. Simple, when we wish to hold on."

~ an excellent lesson from one of the original nautical novelists, Captain Frederick Marryat in Peter Simple

Header: The Long Leg by Edward Hopper via American Gallery

~ an excellent lesson from one of the original nautical novelists, Captain Frederick Marryat in Peter Simple

Header: The Long Leg by Edward Hopper via American Gallery

Sunday, October 21, 2012

Seafaring Sunday: A Virginal Strait

October 21, 1520: Ferdinand Magellan's ships come upon a wide strait between South America and Tierra del Fuego. He names it the Strait of Eleven Thousand Virgins. It is now known as the Strait of Magellan.

Header: An anonymous portrait of Ferdinand Magellan via Wikipedia

Header: An anonymous portrait of Ferdinand Magellan via Wikipedia

Saturday, October 20, 2012

Sailor Mouth Saturday: Parallel

Navigation is key not only to the course and ultimate destination of a ship, but to its safety and the safety of its people as well. Whether by dead reckoning or GPS, good navigation gets the job done. Bad navigation can lead to the worst kind of tragedy. For the most part, today's word is all about finding safe harbor at the end of a cruise.

The word in modern form comes from Ancient Greek where parallassein meant to vary according to Webster's. Para meant beyond and allassein meant to change. You have to admit it is a curious mix but, at this stage in the etymology game, all we can do is go with it.

Essentially, whether at sea or on land, parallel is a word for lines that go out and continue at an equal distance from one another. For the purpose of navigation, parallels are imaginary lines that circle the globe in equidistant patterns marching north and south from the equator. There are ninety such lines in each hemisphere. In this sense, parallel was sometimes used in place of or interchangeably with latitude. "We shall proceed on a course parallel of the Azores."

Similarly, but not quite the same, the term parallel of latitude was used to indicate a circle parallel to the equator passing through a specific, known place such as a city or island. Admiral Smyth tells us in The Sailor's Word Book that the Arabic word for this is almucantar, which has a nice ring to it, I think.

A parallelogram is, of course, a kind of quadrilateral figure whose opposites sides are equal and parallel to one another. A parallelopiped - say that three times fast - is a prism made up of six parallelograms. Made of sometimes clear, sometimes colored glass, these were often set in the top decks of large ships to allow refracted light to shine down to lower decks. A lovely replica of this kind of clever prism is available at National Geographic online.

Parallel sailing is navigation which takes a ship as nearly along a parallel as possible. Parallels of declination are secondary circles parallel to the celestial, not the global, equator. These are used in astronomy as well as navigation.

This last definition of the word naturally leads us to a discussion of another navigational term: parallax. I'll leave it to Admiral Smyth to explain:

An apparent change in the position of an object, arising from a change of the observer's station, and which diminishes with the altitude of an object in the vertical circle. Its effect is greatest in the horizon, where it is termed the horizontal parallax, and vanished entirely in the zenith.

It is easy to imagine that aboard a ship in movement, parallax would come into play often. This in particular when navigating by heavenly bodies such as planets, the sun or the moon. As the good Admiral notes in his entry on this word, the stars are at such a distance from the earth that there is no appreciable parallax either with the naked eye or the instruments available before the 20th century. Annual and diurnal parallaxes relating to the observation of a star from various points on our globe are now more easily discerned with modern technology. To a large degree, however, these are once again issues for astronomers, not navigators.

And so enough of parallels and parallaxes for one day. Were you midshipmen or ship's boys, I'd send you below to write a letter to your mothers. But the Brethren are seasoned sailors, and so I'll raise a mug of grog with ye, mates, and bid you a fair Saturday one and all.

Header: A well crafted, piratical weather vane from the Great Lakes region via the Under the Black Flag team (see sidebar)

The word in modern form comes from Ancient Greek where parallassein meant to vary according to Webster's. Para meant beyond and allassein meant to change. You have to admit it is a curious mix but, at this stage in the etymology game, all we can do is go with it.

Essentially, whether at sea or on land, parallel is a word for lines that go out and continue at an equal distance from one another. For the purpose of navigation, parallels are imaginary lines that circle the globe in equidistant patterns marching north and south from the equator. There are ninety such lines in each hemisphere. In this sense, parallel was sometimes used in place of or interchangeably with latitude. "We shall proceed on a course parallel of the Azores."

Similarly, but not quite the same, the term parallel of latitude was used to indicate a circle parallel to the equator passing through a specific, known place such as a city or island. Admiral Smyth tells us in The Sailor's Word Book that the Arabic word for this is almucantar, which has a nice ring to it, I think.

A parallelogram is, of course, a kind of quadrilateral figure whose opposites sides are equal and parallel to one another. A parallelopiped - say that three times fast - is a prism made up of six parallelograms. Made of sometimes clear, sometimes colored glass, these were often set in the top decks of large ships to allow refracted light to shine down to lower decks. A lovely replica of this kind of clever prism is available at National Geographic online.

Parallel sailing is navigation which takes a ship as nearly along a parallel as possible. Parallels of declination are secondary circles parallel to the celestial, not the global, equator. These are used in astronomy as well as navigation.

This last definition of the word naturally leads us to a discussion of another navigational term: parallax. I'll leave it to Admiral Smyth to explain:

An apparent change in the position of an object, arising from a change of the observer's station, and which diminishes with the altitude of an object in the vertical circle. Its effect is greatest in the horizon, where it is termed the horizontal parallax, and vanished entirely in the zenith.

It is easy to imagine that aboard a ship in movement, parallax would come into play often. This in particular when navigating by heavenly bodies such as planets, the sun or the moon. As the good Admiral notes in his entry on this word, the stars are at such a distance from the earth that there is no appreciable parallax either with the naked eye or the instruments available before the 20th century. Annual and diurnal parallaxes relating to the observation of a star from various points on our globe are now more easily discerned with modern technology. To a large degree, however, these are once again issues for astronomers, not navigators.

And so enough of parallels and parallaxes for one day. Were you midshipmen or ship's boys, I'd send you below to write a letter to your mothers. But the Brethren are seasoned sailors, and so I'll raise a mug of grog with ye, mates, and bid you a fair Saturday one and all.

Header: A well crafted, piratical weather vane from the Great Lakes region via the Under the Black Flag team (see sidebar)

Friday, October 19, 2012

Booty: Is That A Gun In Your Pocket...

I've mentioned The Pirate Museum in St. Augustine, Florida on more than one occasion. Founded by the intrepid Pat Croce, the place is literally full to bursting with authentic artifacts that speak to the pirate history of the New World. It's a wonderful place, and I highly recommend it to any of the Brethren who have a chance to drop by online and especially in person (tell 'em Pauline sent ya).

If you're longing of a bit of history to bring home with you, the Museum is more than obliging. They have a gift store on site, of course, but their online store makes it easy for anyone anywhere to own a little replica of various eras of pirate history. They also have weekly specials that allow for even more latitude in spending.

A great example is the replica flintlock pistol pictured above, which caught my eye on Facebook and just happens to be the Museum's deal of the week.

The original was constructed in 1770 by London gunsmith Bunney. The piece is small, allowing it to be concealed easily. This would have been of value when going ashore to negotiate with local smugglers or when boarding what may or may not be a friendly ship.

The pistol reminds me of nothing so much as the Gentleman Laffite in New Orleans. How very gauche it would be to tote firearms to the Opera or a Black & White Ball. But a man in the racketeer's line of work can't be too careful; a colchemarde and an easily concealed pistol would put one's mind at ease on an evening out. Or when sneaking into the city under cover of night for a visit to one's mistress...

Happy Friday, Brethren! Fair winds and following seas until again we meet (hopefully tomorrow for Sailor Mouth Saturday).

Header: Replica flintlock pistol vie The St. Augustine Pirate Museum

If you're longing of a bit of history to bring home with you, the Museum is more than obliging. They have a gift store on site, of course, but their online store makes it easy for anyone anywhere to own a little replica of various eras of pirate history. They also have weekly specials that allow for even more latitude in spending.

A great example is the replica flintlock pistol pictured above, which caught my eye on Facebook and just happens to be the Museum's deal of the week.

The original was constructed in 1770 by London gunsmith Bunney. The piece is small, allowing it to be concealed easily. This would have been of value when going ashore to negotiate with local smugglers or when boarding what may or may not be a friendly ship.

The pistol reminds me of nothing so much as the Gentleman Laffite in New Orleans. How very gauche it would be to tote firearms to the Opera or a Black & White Ball. But a man in the racketeer's line of work can't be too careful; a colchemarde and an easily concealed pistol would put one's mind at ease on an evening out. Or when sneaking into the city under cover of night for a visit to one's mistress...

Happy Friday, Brethren! Fair winds and following seas until again we meet (hopefully tomorrow for Sailor Mouth Saturday).

Header: Replica flintlock pistol vie The St. Augustine Pirate Museum

Labels:

Booty,

Jean Laffite,

New Orleans,

Pat Croce,

Pistol

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Lady Pirates: Colonel Tangier's Lady

A lot is going on, as usual, including a very sick kiddo at my house. But rather than completely forgo a post, here is one from the archives: the fascinating story of Martha Tunstall Smith and her "whaling design". I am indebted to Joan Druett and her incomparable book on women at sea She Captains: Heroines and Hellions of the Sea as primary research material.

Almost as soon as the Coastal areas of New England were developed by European settlers, and certainly prior to that by Native people, whales were big business. They were even bigger business for smugglers. By as early as 1650, enterprising men and some intrepid women were involved in what they knew as a "whaling design". Essentially, they negotiated with the local Montauk, who regularly harvested whale carcasses from local beaches, to share the bounty of the sea. The Europeans would be given the blubber to boil down for salable oil in return for assistance with butchering the enormous bodies. This went on for about fifty years with one Reverend James Southampton being among the most prominent "designers."

By the early 1660s, others had gotten in on the action and the market was so good that actual whaling expeditions needed to be mounted. Again the Native people, both men and women, were recruited to put out to sea in cedar boats provided by their European employers. They were also given iron harpoons and their skill brought in even more valuable whale oil. To such a degree, in fact, that the heads of these new whaling conglomerates decided they were tired of paying English taxes on their goods before they were shipped back to England. As direct trade with any other European country was banned by the English crown, the whalers took to the ancient art of smuggling.

Enter Colonel William Smith who would become known locally, and possibly derisively, as Tangier. Smith seems to have been an adventurer who fought Barbary pirates at one point; thus his nickname. He told tales, probably very tall, of being made English Governor of Tangiers. The truth is that he had most likely been nothing more than a prisoner of that state, but how would the colonial bumpkins be able to fact-check his story?

The Colonel came to New York on the coat tails of another soldier, Thomas Dongan, who was made Governor in 1682. Dongan granted Smith extensive land which the Colonel parlayed into a massive estate stretching from the current site of JFK International Airport to Little Neck Bay. He called his holding St. George's Manor and, to top off his good fortune, he married a local woman who was already involved in the profitable whaling consortium.

Martha Tunstall was probably a native of New York. The year of her birth and the circumstanced of her youth are lost to us, but some interesting facts survive. Her family name is one of those listed in a complaint made by the afore mentioned Reverend Southampton about the poaching not of whales bu of "ye Indians" who were hunting those whales. Evidently the Tunstall family, or one or more of its members, was working on a "whaling design" of their own and, needing good help, they stole employees from the good Reverend.

By the time Martha married Smith some time prior to 1679, she was a well known and sought after "wise woman" in the greater New York area. Some of her recipes, written in a journal marked Receipts, have survived. They cover diverse ailments from simple blood blisters (apply the fat of a lamb and wrap in gauze) to more troublesome pains like broken bones, deafness and this concoction to bring down a fever:

Dry and pulverize the lungs and liver of a frog. Mix the powder in rum and drink this down. If the fever does not subside repeat a second and third time.

Martha may have been a midwife as well as she notes the names of mothers and children with dates and times in her book of "receipts". She herself was giving birth to children almost immediately after her marriage to the Colonel, but this did not stop her work in the whale oil trade or on her estate. Smith's vast holdings allowed him to live like a virtual Lord and it seems that his wife, and possibly her family, no longer had to recruit Natives from other whalers. Since their estate had, at least in part, been purchased from local tribes, there were a number of able bodied men prepared to go about the mistress' business. The oil was boiled down, barreled and shipped via smuggling vessels to the West Indies where it was traded not only for coin but for rum, cocoa, sugar and tropical fruit.

The bottom fell out of the Smith's boat so to say when Governor Dongan was replaced by Sir Edmund Andros. The new Governor moved his capitol to Boston and put New York colony under the charge of Lieutenant Governor Nicholson. He was an extremely unpopular leader, imposing more taxes and harsh penalties for non-payment, particularly on the middle class. In 1689, when James II was ousted by his daughter and son-in-law back in England, local New Yorkers staged a coup. They appointed Captain James Leiser of Fort James as their leader and marched against the owners of large estates. This included St. George's Manor.

Nicholson turned to these landowners for help and some of them responded. The result was a lot of burning and ransacking that accomplished very little. Smith had the good sense to stay out of it, sending word to the Lieutenant Governor that he could not help in any way. Nicholson finally threw up his hands and returned to England. Uprisings of one sort or another continued, however, until the new Governor - the aptly named Henry Sloughter - arrived and put things in order with brutal efficiency. Leiser and many of his associates were summarily hanged.

Meanwhile, the landowners had suffered losses in revenue and property. In contrast to her neighbors, Martha Tunstall Smith seems to have been able to keep her family afloat without much trouble. By now her sons, how many we do not know, were old enough to help in her "whaling design" and smuggling business. Despite the death of Colonel Smith in late 1691 or early 1692, Martha continued to record profits in the vicinity of 300 pounds per year as late as 1707.

This is the last year we have word of Martha and her operation, interestingly in the form of a notation in a tax collector's ledger. The entry lists her having paid "... Nathan Simon ye sum of fifteen pounds, fifteen shillings for act of Madam Martha Smith, it being ye 20th part of all..." What became of Martha, her business and her boys is a question for further research. What we know of Martha Tunstall Smith and her hard headed Yankee work ethic is, at the very least, remarkable.

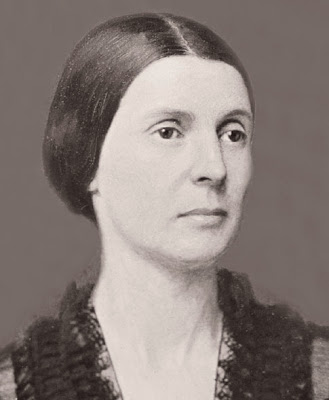

Header: Henrietta de Chastaigner by Henrietta Johnson via 17th Century American Women

Almost as soon as the Coastal areas of New England were developed by European settlers, and certainly prior to that by Native people, whales were big business. They were even bigger business for smugglers. By as early as 1650, enterprising men and some intrepid women were involved in what they knew as a "whaling design". Essentially, they negotiated with the local Montauk, who regularly harvested whale carcasses from local beaches, to share the bounty of the sea. The Europeans would be given the blubber to boil down for salable oil in return for assistance with butchering the enormous bodies. This went on for about fifty years with one Reverend James Southampton being among the most prominent "designers."

By the early 1660s, others had gotten in on the action and the market was so good that actual whaling expeditions needed to be mounted. Again the Native people, both men and women, were recruited to put out to sea in cedar boats provided by their European employers. They were also given iron harpoons and their skill brought in even more valuable whale oil. To such a degree, in fact, that the heads of these new whaling conglomerates decided they were tired of paying English taxes on their goods before they were shipped back to England. As direct trade with any other European country was banned by the English crown, the whalers took to the ancient art of smuggling.

Enter Colonel William Smith who would become known locally, and possibly derisively, as Tangier. Smith seems to have been an adventurer who fought Barbary pirates at one point; thus his nickname. He told tales, probably very tall, of being made English Governor of Tangiers. The truth is that he had most likely been nothing more than a prisoner of that state, but how would the colonial bumpkins be able to fact-check his story?

The Colonel came to New York on the coat tails of another soldier, Thomas Dongan, who was made Governor in 1682. Dongan granted Smith extensive land which the Colonel parlayed into a massive estate stretching from the current site of JFK International Airport to Little Neck Bay. He called his holding St. George's Manor and, to top off his good fortune, he married a local woman who was already involved in the profitable whaling consortium.

Martha Tunstall was probably a native of New York. The year of her birth and the circumstanced of her youth are lost to us, but some interesting facts survive. Her family name is one of those listed in a complaint made by the afore mentioned Reverend Southampton about the poaching not of whales bu of "ye Indians" who were hunting those whales. Evidently the Tunstall family, or one or more of its members, was working on a "whaling design" of their own and, needing good help, they stole employees from the good Reverend.

By the time Martha married Smith some time prior to 1679, she was a well known and sought after "wise woman" in the greater New York area. Some of her recipes, written in a journal marked Receipts, have survived. They cover diverse ailments from simple blood blisters (apply the fat of a lamb and wrap in gauze) to more troublesome pains like broken bones, deafness and this concoction to bring down a fever:

Dry and pulverize the lungs and liver of a frog. Mix the powder in rum and drink this down. If the fever does not subside repeat a second and third time.

Martha may have been a midwife as well as she notes the names of mothers and children with dates and times in her book of "receipts". She herself was giving birth to children almost immediately after her marriage to the Colonel, but this did not stop her work in the whale oil trade or on her estate. Smith's vast holdings allowed him to live like a virtual Lord and it seems that his wife, and possibly her family, no longer had to recruit Natives from other whalers. Since their estate had, at least in part, been purchased from local tribes, there were a number of able bodied men prepared to go about the mistress' business. The oil was boiled down, barreled and shipped via smuggling vessels to the West Indies where it was traded not only for coin but for rum, cocoa, sugar and tropical fruit.

The bottom fell out of the Smith's boat so to say when Governor Dongan was replaced by Sir Edmund Andros. The new Governor moved his capitol to Boston and put New York colony under the charge of Lieutenant Governor Nicholson. He was an extremely unpopular leader, imposing more taxes and harsh penalties for non-payment, particularly on the middle class. In 1689, when James II was ousted by his daughter and son-in-law back in England, local New Yorkers staged a coup. They appointed Captain James Leiser of Fort James as their leader and marched against the owners of large estates. This included St. George's Manor.

Nicholson turned to these landowners for help and some of them responded. The result was a lot of burning and ransacking that accomplished very little. Smith had the good sense to stay out of it, sending word to the Lieutenant Governor that he could not help in any way. Nicholson finally threw up his hands and returned to England. Uprisings of one sort or another continued, however, until the new Governor - the aptly named Henry Sloughter - arrived and put things in order with brutal efficiency. Leiser and many of his associates were summarily hanged.

Meanwhile, the landowners had suffered losses in revenue and property. In contrast to her neighbors, Martha Tunstall Smith seems to have been able to keep her family afloat without much trouble. By now her sons, how many we do not know, were old enough to help in her "whaling design" and smuggling business. Despite the death of Colonel Smith in late 1691 or early 1692, Martha continued to record profits in the vicinity of 300 pounds per year as late as 1707.

This is the last year we have word of Martha and her operation, interestingly in the form of a notation in a tax collector's ledger. The entry lists her having paid "... Nathan Simon ye sum of fifteen pounds, fifteen shillings for act of Madam Martha Smith, it being ye 20th part of all..." What became of Martha, her business and her boys is a question for further research. What we know of Martha Tunstall Smith and her hard headed Yankee work ethic is, at the very least, remarkable.

Header: Henrietta de Chastaigner by Henrietta Johnson via 17th Century American Women

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Sea Monsters: Beautiful Jellies

Jellyfish are some of the most beautiful of the ocean's creatures. In some cases, of course, they can be deadly as well. That doesn't mean that we can't appreciate fantastic photography featuring these strange, primordial monsters.

Over at Photography Blogger, Stephanie Kay-Kok has done just that by posting 20 amazing pictures of these frequently ellusive and always hard to photograph critters. Click over and enjoy; sometimes a picture really is worth a thousand words...

Header: Pacific Sea Nettle Jellyfish, photograph via Wikipedia

Over at Photography Blogger, Stephanie Kay-Kok has done just that by posting 20 amazing pictures of these frequently ellusive and always hard to photograph critters. Click over and enjoy; sometimes a picture really is worth a thousand words...

Header: Pacific Sea Nettle Jellyfish, photograph via Wikipedia

Monday, October 15, 2012

History: The Battle of Camperdown

The Battle of Camperdown, fought between the Royal Navy and a fleet of Batavian (Dutch) ships on October 11, 1797, was part of France's pre-Napoleonic bid to expand their borders. The following was written by Captain William Mitchell of HMS Isis and gives a stunning snap-shot of the aftermath of a sea action:

At 15 minutes past 1, the two fleets were engaging. At half past 1, perceived a Dutch line-of-battle ship with her poop on fire, and she kept engaging some time in that condition, and fired a number of shot at us. She then fell off before the wind. At 2, a Dutch line-of-battle ship struck to us, after engaging us nearly one hour. I sent a boat on board (with Lieutenant William Lamb and a few men) to take possession of her. We kept engaging the enemy's ships as coming up with them. At half past 2, saw the Dutch Admiral's ship dismasted, still keeping firing in that situation for some time, and perceived several of the Dutch ships striking their colours and endeavouring to get away...

During the action we had 2 men killed, the 2nd lieutenant of marines, two midshipmen and 18 men wounded, our mizen topmast shot away, fore and main bracess, mizen stay and several shrouds and back stays. Boats and sails much damaged, small bower anchor broke by a shot, coppers rendered useless, a number of shot in our hull, and lost our jolly-boat by the squally weather.

Header: The Battle of Camperdown by Thomas Whitcombe c 1798 via Wikipedia

At 15 minutes past 1, the two fleets were engaging. At half past 1, perceived a Dutch line-of-battle ship with her poop on fire, and she kept engaging some time in that condition, and fired a number of shot at us. She then fell off before the wind. At 2, a Dutch line-of-battle ship struck to us, after engaging us nearly one hour. I sent a boat on board (with Lieutenant William Lamb and a few men) to take possession of her. We kept engaging the enemy's ships as coming up with them. At half past 2, saw the Dutch Admiral's ship dismasted, still keeping firing in that situation for some time, and perceived several of the Dutch ships striking their colours and endeavouring to get away...

During the action we had 2 men killed, the 2nd lieutenant of marines, two midshipmen and 18 men wounded, our mizen topmast shot away, fore and main bracess, mizen stay and several shrouds and back stays. Boats and sails much damaged, small bower anchor broke by a shot, coppers rendered useless, a number of shot in our hull, and lost our jolly-boat by the squally weather.

Header: The Battle of Camperdown by Thomas Whitcombe c 1798 via Wikipedia

Sunday, October 14, 2012

Seafaring Sunday: The Ocean as Muse

Of all the objects I have ever seen, there is none which affect my imagination so much as the sea or ocean ~ Joseph Addison

Header: Sea Breeze by Walter Cox via Old Paint

Header: Sea Breeze by Walter Cox via Old Paint

Saturday, October 13, 2012

Sailor Mouth Saturday: High

High water, high tide, high and dry; many a lubber has been known to use sea-speak that uses the word "high". But just what do these seemingly familiar terms actually mean to a sailor? So glad you asked.

High flood, high tide and high water are often considered one and the same. I see these terms used interchangeably in sloppy nautical fiction. The fact is that if you're writing about any period prior to the 1950s, you better know the difference here. High flood, or flood tide, referred to not the highest point of a tide but when that tide was coming in. The flux of the tide was its flood whereas the beginning of its rise was a young flood, followed by a quarter flood, a half flood, top of the flood and finally high water. High water then being the very zenith of the tide.

The high water mark is the line made by water on the shore when it has reached the point of high water. This mark indicated where the rule of a country's navy began and the rule of land ended.

High tide, in the parlance of, as an example, Jack Aubrey and his crew, would mean a full purse and a time free of care. Admiral Smyth points up another use of the phrase in The Sailor's Word Book:

Constance, in Shakespeare's King John, uses the term high tides as denoting the gold letter days, or holidays on the calendar.

The call "high enough" indicates that goods have reached an appropriate spot when hoisted up over a ship's side. The term may also be used while utilizing a bosun's chair.

High wind can be said to be synonymous with heavy gale; essentially, a force 10 wind. High latitudes are those areas of the globe above the 50th degree. This applies toward either pole.

In gunnery, high could mean tightly fitting the bore of the cannon. A gun is also said to be laid high when her muzzle is too far elevated.

Finally, high and dry most closely resembles its use on land. It of course signifies a ship that had essentially run aground. As the Admiral puts it so eloquently:

The situation of a ship or other vessen which is aground, so as to be seen dry upon the strand when the tide ebbs from her.

Thus Brethren, I will wish you a constant high tide and that you never find yourself high and dry. Happy Saturday to one and all; fair winds, following seas and endless mugs of grog.

Header: Shore Scene by John W. Casilear via American Gallery

High flood, high tide and high water are often considered one and the same. I see these terms used interchangeably in sloppy nautical fiction. The fact is that if you're writing about any period prior to the 1950s, you better know the difference here. High flood, or flood tide, referred to not the highest point of a tide but when that tide was coming in. The flux of the tide was its flood whereas the beginning of its rise was a young flood, followed by a quarter flood, a half flood, top of the flood and finally high water. High water then being the very zenith of the tide.

The high water mark is the line made by water on the shore when it has reached the point of high water. This mark indicated where the rule of a country's navy began and the rule of land ended.

High tide, in the parlance of, as an example, Jack Aubrey and his crew, would mean a full purse and a time free of care. Admiral Smyth points up another use of the phrase in The Sailor's Word Book:

Constance, in Shakespeare's King John, uses the term high tides as denoting the gold letter days, or holidays on the calendar.

The call "high enough" indicates that goods have reached an appropriate spot when hoisted up over a ship's side. The term may also be used while utilizing a bosun's chair.

High wind can be said to be synonymous with heavy gale; essentially, a force 10 wind. High latitudes are those areas of the globe above the 50th degree. This applies toward either pole.

In gunnery, high could mean tightly fitting the bore of the cannon. A gun is also said to be laid high when her muzzle is too far elevated.

Finally, high and dry most closely resembles its use on land. It of course signifies a ship that had essentially run aground. As the Admiral puts it so eloquently:

The situation of a ship or other vessen which is aground, so as to be seen dry upon the strand when the tide ebbs from her.

Thus Brethren, I will wish you a constant high tide and that you never find yourself high and dry. Happy Saturday to one and all; fair winds, following seas and endless mugs of grog.

Header: Shore Scene by John W. Casilear via American Gallery

Friday, October 12, 2012

Booty: Shanty Friday

I finished with my seven week round of radiation yesterday and my brain is basically mush. I've got a fairly grueling post to put up at HQ today as I've committed to a true, three-part tale of innocence and witchcraft (read the first installment here if you are so inclined) and so I won't subject the Brethren to any long ramblings here.

But how about a shanty? Inspired by Blue Lou's recent post on the sea song "Leave Her Johnny," I give you a beautiful rendition by Johnny Collins. I hope it keeps you singing all day. Happy Friday!

Header: A brig and pelicans via the gentlemen rovers at Under the Black Flag (see sidebar)

But how about a shanty? Inspired by Blue Lou's recent post on the sea song "Leave Her Johnny," I give you a beautiful rendition by Johnny Collins. I hope it keeps you singing all day. Happy Friday!

Thursday, October 11, 2012

People: The Portuguese Poet

In the general vernacular of piratical events, the 1660s and '70s were the decades of Henry Morgan and his Jamaica buccaneers. Thumbing their nose at Spanish might, these men pounced on the Spanish Main whose strongholds had been weakened by the Frenchmen from Tortuga. They were a new breed of plunderer, successful, brutal, and facing very little in the way of obstacles on land or sea.

The truth of the matter is that Spain tried to turn the tables on Morgan during this very era and the spearhead of their privateering ventures was a man of Portuguese descent who would style himself the new Morgan. Brash, volital and at first surprisingly successful, Manuel Rivero Pardal would take up the flag against Protestant heresy on the high seas in the name of the Queen Regent of Spain.

Where Rivero came from - aside from Portugal - is open for debate. Philip Gosse lists him in The Pirate's Who's Who as "the vapouring admiral of St. Jago", which may give posterity its only clue to the pirate's origin. Stephan Talty, in his wonderful biography of Morgan Empire of Blue Water, fleshes out the elusive Rivero magnificently going so far as to call him the Don Quixote of pirates: